Wuhan’s Ordeal

One Family in China's COVID Ground Zero

August 12, 2020

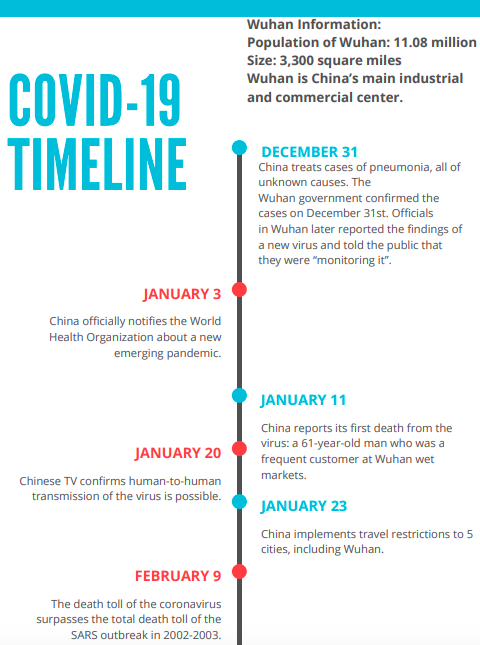

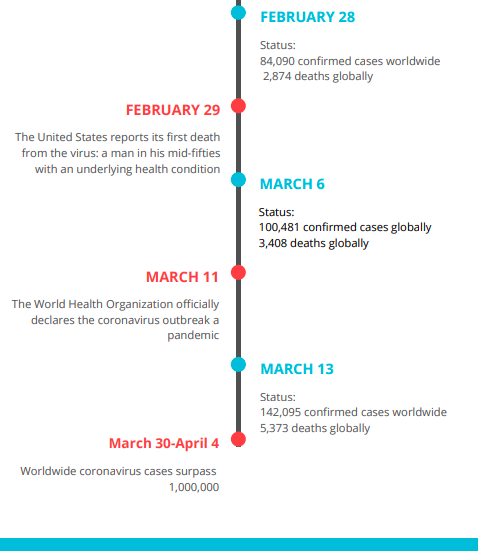

In mid-December, about two dozen people in the Chinese city of Wuhan—capital of Hubei province—were diagnosed with cases of unexplained pneumonia that were soon linked to a new strain of coronavirus. On Jan. 23, with the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) spreading throughout the country, China’s central government imposed a mass quarantine on Wuhan’s 11 million inhabitants. This is the story of one Wuhan family at the epicenter of the pandemic that has claimed the lives of more than 730,000 people, including more than 160,000 Americans. Zhang Wei is a pseudonym; Zhang asked that his real name and those of his wife and daughter not be published because of Chinese government sensitivities over the COVID pandemic.

Before the world as he knew it came to an end in January, Zhang Wei would head off each day to his job at China Construction Bank in Wuhan as he had done for years.

It was the most festive time of the year in China, the countdown to the start of Chinese New Year celebrations. On his daily commute, Zhang would drive past homes and buildings awash in traditional red decorations as city residents prepared for the week-long festival.

Zhang, 48, was born and raised in Wuhan, a sprawling commercial city of lakes and parks, divided by the Yangtze and Han rivers. Except for four years of college, Zhang has lived in the capital city of Hubei province his entire life.

At his bank job, Zhang oversees a department that negotiates large loans with enterprises. That work pays well enough to support an upper-middle-class lifestyle for Zhang, his wife and their 9-year-old daughter. The parents of Zhang’s wife live with them in a 1,500-square-foot apartment in a ten-story high-rise, one of several apartment towers in a gated compound that houses about 700 people.

With the New Year’s holiday looming in late January, life was good for Zhang and his family. The Year of the Rat, as the Chinese zodiac designated the approaching 12 months, seemed to promise more of the same.

Personal ties

I still remember most of my childhood trips to China.

My family and I would always fly 14 hours direct from Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport to Shanghai, China’s largest city and financial capital. From there, we would catch another flight to my mother’s hometown of Xi’an, capital of Shaanxi Province, in northwest China.

I’ve traveled extensively in China, going to many cities and exploring different cultures. But my favorite trips to China were when I would visit my grandmother and her family in Xi’an.

Those trips used to be the highlight of my summer. Every time we saw my grandmother, I would cherish the time I had there before returning to the US.

Each visit, my family and I would stay in my grandmother’s apartment, which was located on the campus of a big college in Xi’an. The streets around us were filled with markets and restaurants of all sorts, and we would always make a point to visit every single one we could find.

Some of my fondest memories of China include exploring the city with my grandmother. We would walk around the crowded malls and plazas, enjoying the bustling atmosphere.

It’s hard to think about them as empty.

Hearing about how the coronavirus has affected almost everybody one way or another in China has been hard for me.

When I first heard about it, I didn’t think it was a big deal. But when the death toll started rising and it was the only thing the global news networks covered, I knew it was momentous.

I thought that because I didn’t live there it would be easy to brush off worries about people I knew getting sick, but I was wrong.

As the coronavirus spread, I found that I got increasingly worried about the health of my family in China. Even though they didn’t live in Wuhan, the thought of people I loved being anywhere close to where the virus started was alarming.

It was even harder for my mother, who was born and raised in Xi’an. She grew up in my grandmother’s apartment and attended school close by. She attended Zhejiang University, located in the city of Hangzhou.

It was there that she met a classmate named Zhang Wei. They’ve been in close contact via the popular Chinese social media platform WeChat ever since. That friendship is what drew my mother and me in a personal way into the tragedy that unfolded in Wuhan early this year.

The first alarms

The first warnings began to reverberate through sites like WeChat late last year.

An emergency notice to Wuhan city hospitals had been shared on social media sites on Dec. 30, “apparently triggering some public panic,” the New York Times reported. The Wuhan government reacted to the rumors the following day, confirming that health authorities were treating dozens of cases of pneumonia of unknown cause.

The rising alarm among Chinese government officials would remain largely secret for the next three weeks. In the first week of January, medical workers in Wuhan hospitals began quietly gathering data about the suspected cause of the pneumonia cases: a highly infectious virus that was somehow linked to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan. Within a matter of days, the doctors made a frightening determination: the virus could be spread from human to human.

On Jan. 20, with millions of Chinese poised to travel to their hometowns and gather with their extended families to celebrate the New Year’s holiday, China’s central government publicly sounded the alarm.

That was the day that the government broadcast network, CCTV, quoted Chinese leader Xi Jinping as warning that the outbreak “must be taken seriously.” Xi called for action to contain the disease. Authorities revealed that new cases had already been detected in the national capital, Beijing, as well as Shanghai and the far southern province of Guangdong. Other cases—many linked to travel to Wuhan—had been reported elsewhere in Asia.

Early on the morning of Jan. 23—two days before my mother’s friend Zhang and his extended family were poised to gather for their traditional New Year’s Eve dinner—the central government in Beijing made a stunning announcement: At 10 a.m. that morning, public transportation in and out of Wuhan would be shut down.

In an effort to prevent further spread of the mysterious illness from Wuhan, the city was to be quarantined from the rest of China and the world.

Zhang and his family awakened to a changed world. The typical anticipation of the New Year’s holidays was replaced by the sense of fear and isolation that fell over Wuhan.

The lockdown begins

In those early days of the quarantine, everything seemed under control. People were still able to leave their neighborhood to get necessities, Zhang said.

“There was flexibility in the first two weeks,” Zhang said. “People could still go drive and shop.”

That changed overnight.

“Two weeks after the lockdown, vehicles weren’t allowed to get onto the road, and you had to get permission from the government to go outside of your compound,” Zhang said.

Business closed. Doors shut. People lost their jobs. And the death toll—in Wuhan and across China—mounted.

Zhang spent his days working remotely and talking to his loved ones on the phone as much as possible. Everyone in China was scared. Talking to people they knew was the only possible therapy, Zhang said

He also took advantage of the time he had by sleeping in and spending quality time with his family. By then, schools had closed, and everyone was working from home.

Nobody imagined how long the lockdown would last.

“I thought that a shutdown of 10-15 days was necessary at the time,” Zhang said. “But it just kept on going.”

In Wuhan, the shutdown was extended in increments of fourteen days. Just when people thought that restrictions would be lifted, they were hit with another two weeks of staying at home.

What started out as a shutdown “just to be safe” would eventually stretch into three months.

“Most of the people expected the shutdown to last a couple of weeks at most,” Zhang said. “We weren’t aware of the severity of the situation at the time.”

There was a lot of anxiety and nervousness during the beginning of shutdown caused by the lack of knowledge that people had. This was the first shutdown that Zhang had ever experienced, and he didn’t know what to think of it.

“Not knowing what was happening or how long we would have to stay home caused a lot of concern,” Zhang said. “It was hard having to speculate all the time.”

Most supermarkets remained open and workers deemed “essential” were still on the job, but everyone else was mostly restricted to their neighborhood or compound. Panic-buying became commonplace, Zhang said. He recalled going out at 5 a.m. one morning and spending $500 on groceries.

Internet shopping services in Wuhan allowed people to buy groceries online, and someone would deliver them to a specific compound pick-up point.

“There were a lot of services that helped you to do purchases,” Zhang said. “They charged some money and arranged the deliveries. There were a lot of different ways for people to get different necessities and they are all very convenient.”

The wet markets had closed because of fears of a link to the novel coronavirus, but supermarkets ran normally throughout the quarantine and were usually relatively full of necessities and supplies. There were no shortages of essential items, Zhang said.

“There is some propaganda that said people in Wuhan didn’t have supplies, but it wasn’t true,” Zhang said. “As long as you knew how to use your phone you could get anything you needed.”

Hospital crisis

Although food wasn’t scarce, medical resources definitely were. Hospital beds filled up fast, Zhang said.

If you had the virus, you might as well be dead if you weren’t able to find a hospital bed. Yet beds were hard to find. Connections through higher-ups in companies were necessary. You had to know the right people, Zhang said.

“You basically could not find a hospital bed at all,” Zhang said. “During this hard period of time, the only way you could survive was to find a hospital bed.”

Public venues such as gymnasiums and stadiums were converted into temporary hospitals to treat patients with mild symptoms of COVID-19. China would eventually create sixteen temporary hospitals that treated 13,000 patients.

Mental suffering

Across China, the fear and lockdowns took a mental toll.

Merry Zhao, a therapist from the Jiangsu province who worked as a volunteer for a national COVID-19 hotline, described the struggles of callers, including severe anxiety about dying and general anxiety and depression. Anxiety was especially high among health care workers who feared contracting the virus.

A study done by three researchers showed that mental health workers were experiencing symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia and distress.

Most people in Wuhan had friends or family members who were impacted by COVID-19, which caused anxiety and depression throughout the community.

Most people could be divided into two categories: those who were personally affected by COVID-19; and those who had close relatives and relationships affected by the virus, Zhang said.

The first group was affected more physically, as their lives were on the line. The second group, however, went through a lot of emotional trauma, Zhang said.

Zhang had two close friends who were impacted by the coronavirus. One of his friend’s parents were infected by the virus. Although the mom survived her month in the hospital and came out healthy, the father died.

Zhang had known these people for a long time, and he shared their pain.

“Even though my friend wasn’t my direct family, the whole process took a toll on me,” Zhang said. “I was really depressed and there was a lot of anxiety.”

One of Zhang’s coworkers was infected with the virus and ultimately died. The man was only 65 years old, but both he and his 85-year-old mother died. This left only two people in their family, which was devastating, Zhang said.

Even for those who didn’t have friends or family impacted by the coronavirus, mental health was still very fragile, Zhang said.

Stories about death were passed around communities, leaving people to wonder what would happen to them or their own families, Zhang said.

When loved ones died, family members were not able to see them until they had been cremated. The hospitals would move their bodies to crematoriums, and families would only be able to pick up a small box of their ashes, Zhang said.

This was especially painful for families, Zhang said.

“Even for the families who weren’t directly impacted, I think that they are all mentally impacted one way or another,” Zhang said. “Anxiety, depression, and irritation were common because of all of the stories flying around, wondering if this would happen to themselves.”

Economic fallout

The weeks of quarantine caused massive damage to the Chinese economy, Zhang said.

Although larger corporations are mostly okay, small businesses are not doing so well.

“I read somewhere that said 40-60% of private small businesses are impacted,”

Zhang said. “The restaurant industry was practically destroyed.”

Even after restaurants and other businesses reopened, people have hesitated to resume life as it existed before the pandemic, slowing economic recovery, Zhang said.

The government has been trying to help by reducing taxes and issuing low-interest loans, Zhang said.

Zhang also has sympathy for the difficulties the pandemic has caused for the government.

“For the government, it’s a very fine line to walk on,” Zhang said. “On one side, they need to control the virus and make sure that people aren’t dying, but on the other side, the economy is a very big measure of how successful the country is.”

Evaluating China’s response

Around the world, the complex challenge facing governments has been how to balance the economic destruction unleashed by quarantines against the need to save lives and reduce the spread of the disease.

It’s a particularly delicate balancing act for China and its system of one-party rule, which has been maintained by delivering consistently high economic growth. In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, the government wants to keep the unemployment rate low, so the country is still stable, but it’s also important to minimize the number of deaths.

Sounding a note of national pride, Zhang said he believes that, compared other countries, China has handled the crisis in the best way.

“I think the way that the Chinese government is handling it is the most effective way,” Zhang said “I agree that under other systems it’s pretty hard to do what the Chinese government did. Different systems can’t enforce the rules and people are not used to being forced to do anything.”

Zhang said this is how the United States and Italy have experienced such high infection rates and total deaths. The governments weren’t able to impose lockdowns like the Chinese government, so people were still going outside and having parties, Zhang said.

In spite of the fact that there has been an ongoing debate in the U.S. and elsewhere about where the coronavirus started, Zhang said he believes that there’s no doubt it started in Wuhan. China should accept responsibility for that, he said.

“There is a lot of blame back and forth about who started the virus,” Zhang says. “Putting all that aside, it’s a fact that it started first in Wuhan.”

In America, there has been a backlash toward China for supposedly violating their citizens’ human rights and refusing to let them out of their homes.

Zhang said he disagrees with this criticism.

“Western society blames China for restricting people and ’violating their human rights,’ but a different angle of that is that it’s the only way to minimize the disease and its impact,” Zhang said. “Most people [in China] don’t think that way and they agree with what the government has done during that period.”

The Trump administration has accused China of keeping the virus a secret for too long and blames the Chinese government for the global spread of the disease, but Zhang said he believes that China has played an important role in the global fight against COVID-19.

“I think what the Chinese government did in providing resources and medical resources to other countries was good, and they did their part,” Zhang said.

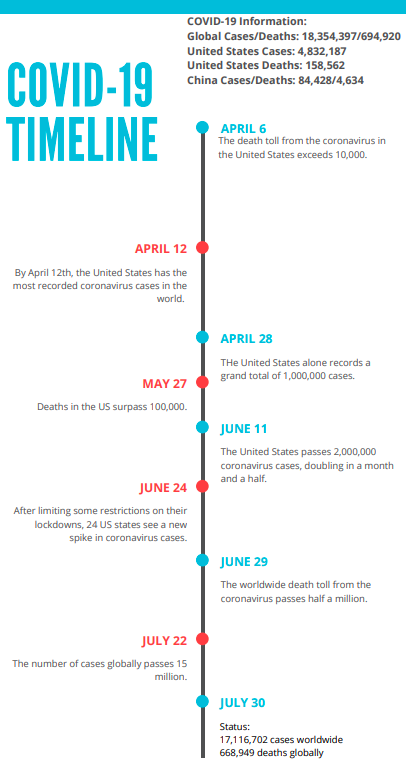

Although China has faced international accusations of underreporting its infections and deaths, the available numbers suggest China has handled the COVID-19 crisis better than the United States.

As of mid-August, according to the Worldometers website, China had experienced a total of 84,668 COVID-19 cases with 4,634 deaths. The United States had reported more than 5 million COVID-19 cases with more than 160,000 deaths.

‘What’s important in life’

Seven months after emerging as the world epicenter of COVID-19, Wuhan has seemingly overcome the virus, Zhang said.

Later in the quarantine, everyone who was required to leave their house on a regular basis was tested. Over time, the improved accessibility of medical care and greater government about COVID-19 calmed fears in Wuhan.

Knowing what was going made it a lot easier to handle, Zhang said.

Although the restrictions were lifted in April, Zhang said he and his family are still required to wear a mask when going out. Some parts of China have experienced a spike in COVID-19 cases, and there is fear of another wave of illness.

The outlook has brightened enough to where Zhang is able to find some positive aspects of the ordeal. He caught up on sleep and got to spend more, quality time with his family. His daughter experienced less school-related stress, which had a positive impact on the entire family. Additionally, Zhang kept his good-paying job.

Most importantly, no one in his family died.

Zhang’s older brother survived a bout of COVID-19, in part because his wife was a nurse and knew exactly what to do.

This brush with family tragedy forced Zhang to rethink his life values.

“It made me think of what’s important in life,” Zhang said. “Money isn’t the most important thing. Family is important.”

Zhang’s greatest fear during the darkest days of Wuhan’s coronavirus crisis was that he would contract the disease and pass it on to his wife or daughter, or his aging parents-in-law.

“I am extremely relieved that my family and I ended up okay in the end,” Zhang said. “I was always worried that something would happen to them.”

Fran • Aug 21, 2020 at 9:03 am

Awesome article Isabel !

Alicia • Aug 12, 2020 at 11:51 am

Great article!!!